Tuvaluan Troubles: What Happens When a Country Sinks?

Statehood, Fishing Rights, and Refugee Status

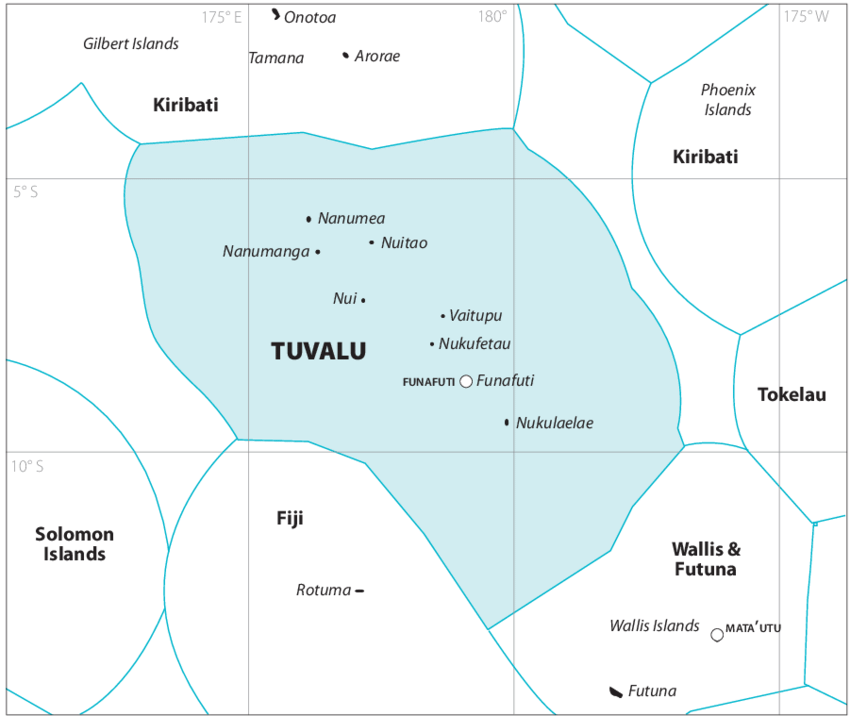

Tuvalu is sinking. The small island nation, home to 11,000 residents, cedes land every day to the Pacific Ocean. Due to climate change, global sea levels are rising at historic rates; some studies suggest that we’ll see sea levels rise more than one meter before the end of the century. This may not seem like much to us, but this presents an epistemic threat to islands like Tuvalu, whose highest point sits a mere 14 meters above sea level.

This was made clear by Tuvalu’s Foreign Minister, Simon Kofe, when he gave a speech to the UN Cop26 climate summit while standing in knee-deep water in November of last year. Tuvalu has struggled to deal with significant coastal erosion on top of rising sea levels, and the government is already preparing for a worst-case scenario in which Tuvalu is completely submerged.

If this were to happen, it would fundamentally challenge how we think of statehood. As enshrined in the 1933 Montevideo Convention, statehood has four qualifications: a permanent population, government, the ability to enter into relations with other states, and a defined territory. This last criterion is a particularly important part of statehood and sovereignty. Think about how all governments collect revenue — through taxes. For almost all human history governmental revenue has been raised via taxes on agriculture, which requires productive land. Moreover, agricultural activity was essential to the survival of any empire because governments don’t last long when people are starving.

With the rise of global trade, agricultural production and land holdings have become less important to the survival of many nation-states. Even so, island polities like Tuvalu depend on the presence of physical land. Revenue streams which don’t seem tied to the land are bound to it. Tuvalu’s economy is a great example of this. As written in international maritime law, nations generally have sovereign rights over the waters up to 200 nautical miles off their coast. Nation-states have the right to control and regulate all economic activities within this Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Tuvalu is dependent upon the revenue generated by selling fishing licenses to foreign groups who want to fish within Tuvalu’s EEZ; in 2013 this revenue made up 45% of the country’s GDP. You wouldn’t think that fishing rights in the ocean would be determined by land holdings, but the rights to a particular patch of ocean are determined by that patch’s proximity to a state’s coastline. If Tuvalu goes under there would be no coastline, and consequently no basis for a claim to their EEZ.

A New Refugee Crisis

The fate of the Tuvaluan people matters more than any issue about statehood or governance. They face a myriad of challenges due to the devastating effects of climate change. For example, warmer seas, caused by climate change, create larger storms. If a storm like Katrina hit the island, there would be no way to rebuild what was destroyed. Moreover, increased sea levels have led to more ocean water leaching into aquifers, causing crop failures and food insecurity. This has also made most of the water on the island unsafe to drink. Residents have to rely on rainwater for sustenance, and in times of drought the island imports fresh water from Australia and New Zealand. All told, life on the island has become increasingly difficult and dangerous, leading many people to seek futures elsewhere. They become climate refugees.

The title “climate refugee” is a slight misnomer because, unlike most groups we call “refugees,” these migrants don’t have refugee status. Per international agreements, refugees are people who are “unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” Individual governments have their own definitions for the immigration laws, but generally their definitions hinge on the idea that to be a refugee one must be persecuted in their home country. Tuvaluans are displaced by issues of climate, not persecution, and so they do not count as refugees.

This matters because refugees have, in many cases, easier access to immigration to safer countries. Refugees can apply for asylum and permanent residency in nations which can secure their safety, while mere migrants have no such avenues for immigration. Moreover, refugees are protected by non-refoulment obligations; international law states that refugees cannot be deported to countries where they would face violence, torture, or persecution. Climate migrants, on the other hand, can be deported back to Tuvalu without a second thought. While international courts have made promising rulings, today most wealthy nations are hesitant to accept climate migrants. This is true even though many of the countries refusing these migrants entry, such as the US, UK, and Australia, have caused and even benefited from the climate change forging them to leave their homes.

Even after taking into account seawall construction, economic growth, and population movements, research indicates that climate change could sink between six and ten pacific island nations. This makes up only a small fraction of people who will be affected by climate change; the World Bank estimates that within 30 years there could be close to 150 million climate migrants in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America alone. This represents a challenge the likes of which the world has never seen, and it’s up to us whether we sink or swim.

Tuvalu is not sinking, it's actually growing in size. Although the shape of its coastline is changing which can displace some people. Linked in the BBC article you cite is this article (https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn27639-small-atoll-islands-may-grow-not-sink-as-sea-levels-rise/?ignored=irrelevant#.VX4fFGB3uCQ) which references this satellite imagine paper in Geology (https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article-abstract/43/6/515/131899/Coral-islands-defy-sea-level-rise-over-the-past?redirectedFrom=fulltext)

Sea levels have been rising "Funafuti Atoll, in the tropical Pacific Ocean, has experienced some of the highest rates of sea-level rise (∼5.1 ± 0.7 mm/yr), totaling ∼0.30 ± 0.04 m over the past 60 yr."

But the island is not sinking "Despite the magnitude of this rise, no islands have been lost, the majority have enlarged, and there has been a 7.3% increase in net island area over the past century (A.D. 1897–2013)."