Libertarianism's Lack of Justice

Ever wondered why your libertarian roommate steals food from the fridge?

Libertarianism is facing a crisis. As a theory primarily concerned with property holdings, it deals mostly with issues regarding how things may be created, bought, and sold. However, as anyone who grew up with older siblings knows, any theory of just property holdings must answer the problem of what to do when property is stolen. While libertarians might have an idea of what justice requires when your roommate drinks all of your White Claw Surges, the theory generally fails to answer the harder questions of injustice, like how to deal with centuries-old systems of oppression and genocide. To get a better picture of why this is true, we need to start our story with the most influential libertarian thinker of the last 50 years: Robert Nozick.

NOZICK’S POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY

Nozick applies three principles of justice to holdings. First, the principle of justice in acquisition. This includes issues of how property comes to be owned and what property can be owned. While his principle is more nuanced than this, we can think of a property acquisition as just if in the process of acquiring the property no one’s rights were violated (nobody was murdered, coerced, enslaved, robbed, assaulted, etc.).

Second, the principle of justice in transfer. This one is pretty simple; it only concerns how property holdings can be justly transferred from one person to another. In Nozick’s view, a holding can be justly transferred between two parties if both parties agree to the transfer without the presence of coercion.

One important point about these first two principles: these are principles of justice with a historic lens. Any given distribution of property is just as long as it comes about by just means. It doesn’t matter if the distribution is wildly unequal or produces little utility, we can look through the record books and as long as in each transaction that got us to the point the first two principles were upheld, the distribution is just.

Nozick’s third principle of justice deals with what happens when historical analysis shows us that the current distribution is unjust. Any theory of just property holdings must have a method of dealing with injustice, and this is especially true for a political theory developed and exercised in the United States. The US was founded as a slave state, and even to this day we feel the ramification of centuries of legal disenfranchisement, theft, and racial murder. Millions of dollars of Black wealth have been destroyed, often through violent means, to enrich white Americans. Moreover, almost every acre of land in the United States was stolen from indigenous people who, by and large, were killed in genocides or forced to assimilate to American culture.

Now, while my co-contributor might not feel like reading books written by people he disagrees with, I actually took the time to read Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Nozick, in his 372 page book, dedicates all of a page and a half to the problem of rectifying injustice. He writes that he “does not know a suitable principle of rectification” (ASU, 152) and that he can only “suppose that theoretical investigation will produce [one].” (ASU, 152) However, despite not being a fully fleshed out theory of rectification, Nozick does state that rectification would involve counterfactual analysis of what would have happened had the injustice not taken place (this process may involve the use of a probability distribution of potential likely outcomes). If the actual distribution of holdings doesn’t match the distribution sans injustice, then the corrected distribution “must be realized.” (ASU, 153) It’s plausible to assume that the process of rectification may take the form of reparations, however, alternative methods of property redistribution might be possible.

REPARATIONS AND LIBERTARIANISM

Just because one of the most influential political minds in the last 100 years (and the intellectual re-founder of American libertarianism) expressed support for reparations, that doesn’t mean everyone else has jumped on board. Today, roughly half of Americans and ninety percent of Republicans oppose reparations. While the issue has gained some attention in the House, it’s unlikely that anything tangible will come to fruition..

Why is the libertarian party not trying to ameliorate these issues? Well, part of the issue is that they’re too busy trying to abolish child labor laws and repeal the civil rights act. But why are they more focused on re-legalizing racial discrimination? The answer to that question might be found when we look at who libertarians are. 94% of libertarians are white and nearly half of libertarians make over twice the US median income. It makes sense why libertarians don’t often think about rectifying historic injustices when they’re the people who have largely benefitted from those injustices.

Moreover, the libertarian agenda is uniquely opposed to reparations and similar measures of rectification. Most likely there are many people, particularly wealthy white Americans, who would not want to give up any of their personal wealth to pay for just reparations. Assuming that a particular slate of redistributionary measures is just, there must be an entity with the power to force people to give up their assets in such a program. However, the libertarian project is deeply distrustful of entities, like governments, which have this type of enforcement power. Libertarian theory also includes no means of publicly deliberating to determine what slate of redistributional policies would be just at all!

IDEAL THEORY

This critique of libertarianism can be expanded to one of ideal theory altogether. Ideal theories are theories that try to determine what the perfect society looks like. Nozick’s work is a great example of this — he goes into his mind palace, thinks about his principles of justice, builds a minimalist state based off those principles, and publishes a book on it without seriously considering how to deal with injustice or how to transition our unjust world to his “just” one. As a result, libertarian efforts to cut social spending, abolish affirmative action, and deny reparations often work directly against any real-world conception of justice. It’s ironic, Nozick argues for a theory of justice that has a historic lens, yet his followers refuse to apply a historic lens to the injustices that we’re actually grappling with today.

Non-ideal theory, on the other hand, takes historic injustices and flaws in human nature into account. This type of theory focuses on how we can address the injustices occurring in our society as it stands today, and as such it is more applicable to political issues. Rather than being fodder for philosophy professors on their lunch break, non-ideal theory is the work of activists and politicians on the ground.

A problem with libertarianism as it stands is that its proponents confuse ideal theory with non-ideal theory. Ideal theory is necessarily theoretical. Its project is that of creating a perfectly just society from the ground up. Of course, our actual society is not just today, nor has it ever been. Adopting libertarian policy proposals is, at best, like putting a fresh coat of paint on a house riddled with termites. At worst, policies like cutting the social safety net and repealing the civil rights act will exacerbate the effects of these injustices.

At minimum, before the theory can be implemented in the real world there must be some standard of rectifying the difficult injustices. This means going further than having a system of justice that rectifies a mugging that happened last Wednesday. Libertarians need a compelling conception of justice that recognizes the importance of rectifying for the oppression and genocide that defines American history. The libertarian party in particular needs a means of rectifying for the harms of injustice because its lord and savior, the free market system, condones and creates horrific human rights abuses that are difficult to rectify.

MODERN DAY SLAVERY

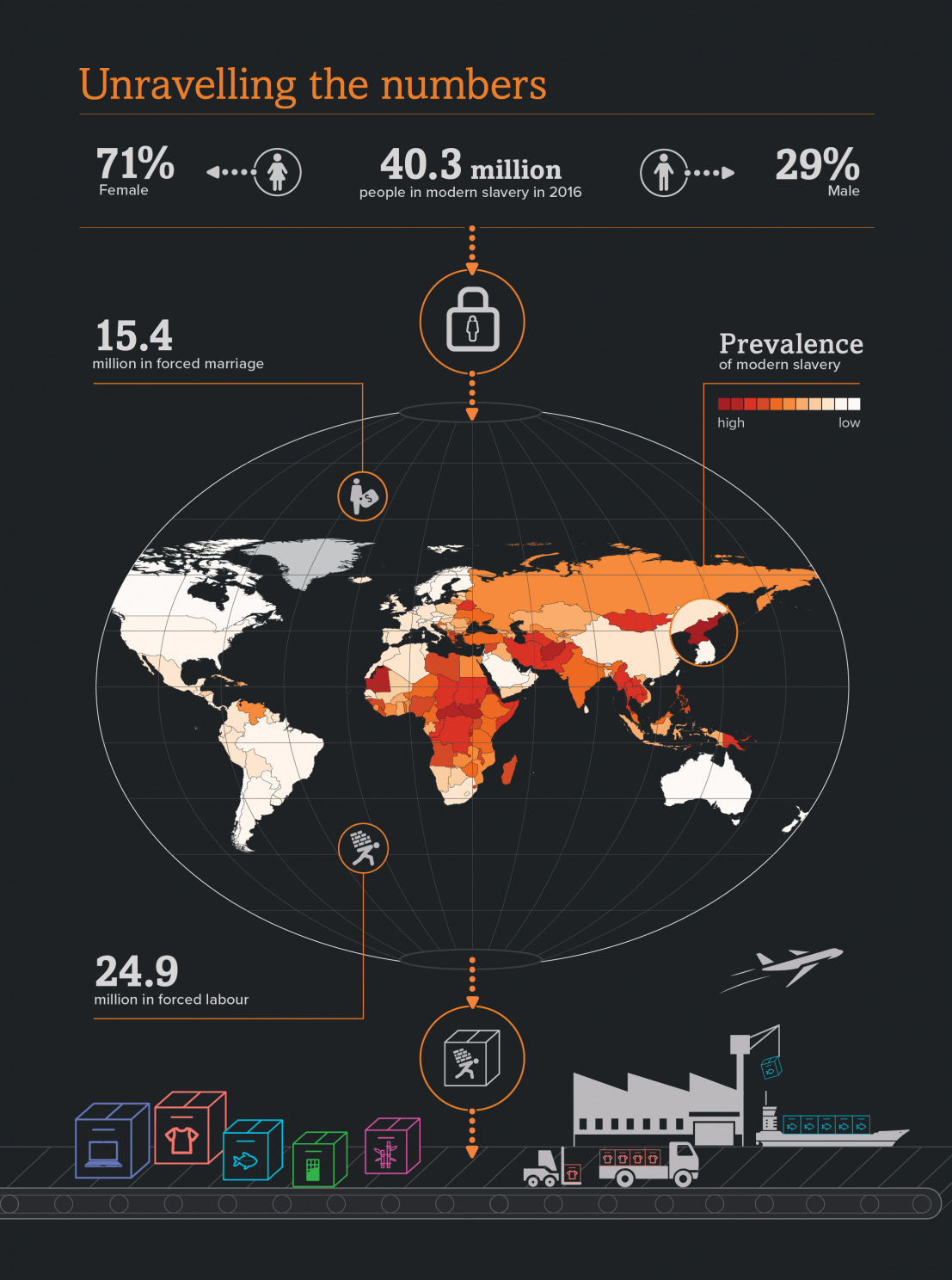

Over 40 million people are enslaved today, more than at any other time in human history. Among these victims are 25 million people in forced labor camps and 15 million people, mostly women, in forced marriages. Roughly a quarter of these slave are children. This slavery takes place in many forms; one form common in wealthier nations like the US is the exploitation of migrant workers.

When migrant workers are abused or have their pay stolen, they rarely have the resources to contact authorities. In the US, many foreign-born workers do not speak English, and many more cannot seek legal representation without fear of economic ruin or deportation. Beginning in 2006, marine construction firm Signal International, in a scheme led my immigration lawyer immigration lawyer Malvern C. Burnett and Indian labor recruiter Sachin Dewan, lured hundreds of workers to southern Mississippi shipyards to work as welders. However, after paying the recruiter upwards of $10,000 to ensure safe passage and access to a green card, they were forced by armed guards into labor camps with no green card or legal status. Up to 24 workers shared a sleeping area the size of “a double-wide trailer.” Fortunately, in this case Signal International was required to pay a historic $14.4 million settlement to the victims, however, human trafficking cases continue to occur across the US.

International waters are often depicted as a libertarian “wet” dream. Government regulators can’t easily enforce laws in the middle of the ocean, and laws in the open ocean are generally much more lax than on land. This is part of the reason some libertarians are pushing for seasteads, oceanic city-states which can skirt government policy by not being a part of any existing state’s territory. But before you book a one-way ticket to Honolulu Jr., you could be aware that international waters are also rife with theft and enslavement.

Thailand’s fishing industry is a particularly horrific example of this. According to a survey conducted by Human Rights Watch, one in five laborers “work against their will with the menace of a penalty preventing them from leaving.” Living conditions on these ships are hellish. Workers are allowed four hours of sleep a day, two during daylight and two during the night. Sick crewmembers are cast overboard and left to drown. Slaves who disobey their masters are often beheaded or locked below deck for days without food. Many of these slaves were drugged before being dragged onto boats just minutes before leaving port.

These abuses occur due to the nature of the free market. Ship captains know that laborers are too poor to pursue legal damages (assuming they ever escape), so they don’t fear punishment. Furthermore, the process of pursuing damages for this enslavement is too expensive for law firms to take on pro bono. Some non-profit organizations are doing work to free currently enslaved people, but that doesn’t change the fact that the powerful corporations profiting from this slavery are happy to turn a blind eye.

This isn’t to say that massive rights abuses don’t occur at the hands of state power. Everyone knows about, or at least should be made aware of, the long history of genocides that have occurred, and that are still occurring today, under the authority of governments around the world. However, a libertarian political theory needs to account for the injustices caused by the free market. The principle of justice in rectification needs to answer questions of how to account for multi-generational slavery, how class-based discrimination can be rectified, and what to do about the profits made off the labor of since-executed slaves, among others. Moreover, this theory must have actual, practical solutions that would prevent injustices from happening in the first place because, as we can quite clearly see, the unfettered free market is happy to perpetuate these abuses.

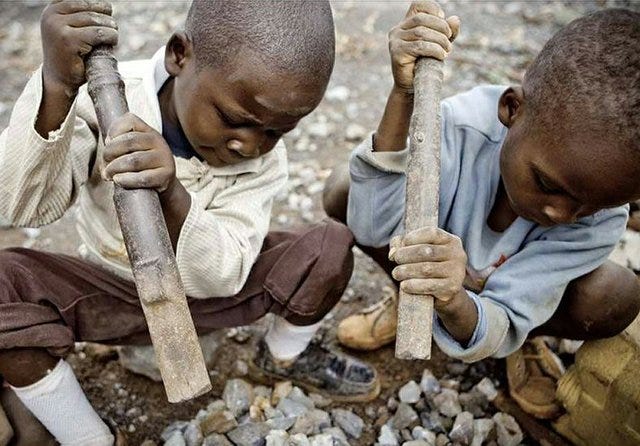

However, the crisis of libertarianism isn’t merely that the theory must find a way of preventing slavery and dealing with complex justice in a free market system. The issue is that libertarianism as it exists in the US is more concerned with the “oppression” Elon Musk faces when he pays taxes than the child labor and slavery that he profits off of (and no, we’re not talking about his family’s emerald mine). Cobalt is an essential component of lithium-ion batteries, which are in smartphones, laptops, and Tesla’s lineup of electric cars. More than half of this cobalt is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Cobalt mined in the DRC has a terrible track record when it comes to human rights. The relationship between contracted miners and mine-owners is like “slave and master.” Workers, often children as young as six years old, toil for 6 days a week making less than $1.50 a day. They face incredibly dangerous working conditions; one class-action lawsuit currently in the US Federal Court system claims that companies like Tesla, Apple, and Google deliberately “turned a blind eye” to children losing limbs and being killed in tunnel collapses. Many children are forced to work at risk of death or serious harm — and these are only the cases we know about.

While in theory Tesla has taken steps to ethically source cobalt, it’s unclear how productive these steps have been. Moreover, this doesn’t change the fact that the libertarian project still fails to highlight or rectify this system of oppression. Talk to libertarians in the US and slavery induced by the free market is simply not a concern. In fact, in many cases libertarians like my co-contributor try to paint this oppression as moral!

I can see him in the comments now. He’ll say, “the children (at least those who aren't forced at risk of death) volunteer to drop out of school and start mining. If you prevented them from mining, their families might starve! Would you rather their families starve?” Of course no, nobody is pro-starvation. The issue lies not in the children who must work to feed their families, but in the fact that libertarianism tries to abstract away from the real life circumstances of oppression to justify these mining practices. Let’s pretend, for a second, that the fact these children must risk serious injury mining to feed themselves and their loved ones is in no way tied to centuries of colonial exploitation (because libertarianism simply refuses to address the historic injustices that libertarians themselves reap the benefits of). In the libertarian ethic, the most oppressed man in the equation is multi-billionaire Elon Musk because he’s paying millions of dollars in taxes, which is essentially the same as forcing him to labor (ASU, 172). On the other hand, the children working in mines are in no way oppressed.

SO WHAT NOW?

Before moving on to looking at some possible principles of justice in rectification let’s go back over the charges levied against libertarianism. First, the theory lacks an adequate method of rectifying injustice. There is no current push in libertarian politics to address long-standing historic injustice and its effects. Maybe this is because libertarians are largely not on the receiving end of racial discrimination, or maybe this is because they’re more focused on cutting social services. I’m not in a position to say why the libertarian party is ignoring these issues. Second, the theory doesn’t seem particularly interested in dealing with the consequences of ongoing slavery caused by the free market. In an ideal world the theory doesn’t need to address this. However, in our non-ideal reality we must grapple with the reality of injustice.

It’s not fair to say that no libertarians are concerned with injustice. I’m sure all of you in the comments are more empathetic and informed than I could ever be. There are two main libertarian “responses” to injustice that I should preempt. First is arbitration. Some more extreme libertarians are in favor of abolishing the entire American court system, and I address this point to them. If arbitration was going to be a practical solution to these types of injustices, we would see arbitration being used today to deal with injustices that governments are happy to overlook. Even the crowding out effect of government court systems, we would expect to see something at least.

The reason Thai fishing boats aren’t held responsible for their business practices isn’t because international waters are too tightly regulated (because regulations are rarely enforceable), it’s because you can’t make a profit fighting for the rights of some of the poorest people on earth. The adage “the invisible hand will solve it” doesn’t cut it when the free market is driving and exacerbating slavery.

On a similar note, the response “slavery happens because the market isn’t free enough” is not compelling either. It reminds me of communists who refuse to recognize the need to prevent dictatorships and gulags because “the USSR wasn’t real communism.” Of course no ideology explicitly supports slavery or imprisoning political dissidents in their perfect hypotheticals. The complexities of the real world mean that no ideal theory will be instituted exactly as planned, but that doesn’t mean we cannot gain insight into the general flaws of certain ideologies by looking around us. Vast differentials in wealth and power created and perpetuated by the free market contribute to oppression and coercion that must be addressed, even if addressing this coercion isn’t profitable.

Second, many libertarians would point to the effective altruism movement as evidence that they care about correcting for injustice. While trying to maximize the benefit of every dollar donated to charity is a noble goal, it’s not the same thing as correcting for injustices. Reparations correcting for the impacts of slavery might incluse mass payments to Black Americans by White Americans who probably don’t want to pay. Correcting for the theft and murder of American westward expansion may require the same.

Of course, it’s a little unfair to point out libertarians as uniquely failing to address these issues. Neither major political party cares much for reparations, and modern slavery is such an issue because so many powerful governments and corporations are willing to turn a blind eye. If you care about human dignity or human rights you should be appalled by this, and I’m not saying that libertarians aren’t concerned. However, almost all of you have been directed here by my co-contributor’s dad’s libertarian blog, so a disproportionate number of you reading this are libertarians. Moreover, this problem is particularly apparent in libertarian ideology — at least Democrats and Republicans alike in the DOJ are working to free human trafficking victims as opposed to merely trying to abolish the DOJ.

RESOURCES

Thanks to those of you who stuck around to the very end. Here are some resources I would suggest checking out if you’re more interested in learning about anything I’ve mentioned in this article.

I highly recommend reading Anarchy, State, and Utopia if you haven’t already. Even as someone who disagrees with Nozick generally this book greatly shaped my political thinking. Chapter 7 is most relevant to this article, but I recommend reading Part 1 for a fuller understanding of his conception of the minimal state

I also highly recommend reading Charles Mills’ work The Racial Contract. This book critiques political philosophy generally for being too wrapped up in ideal theory. If you’re interested in understanding philosophy as a historical project this is the book for you.

I only discussed a small portion of the slavery that occurs today, and largely did not touch on the issue of modern day chattel slavery, which occurs most commonly in Libya. I also suggest starting off reading this report by Human Rights Watch if you want to learn more about slavery in Thai fish markets and this paper by Benjamin Sovacool of the University of Sussex on Congolese child labor in cobalt mines. This New Yorker article also makes for a decent read.

Thank you for reading if you’ve made it this far, and if you like this post please subscribe for more like it! I’m making it a new semester’s resolution to post at least once a week, with a more in-depth post once a month, so keep on the lookout for those!

This is a good response to a particular, albeit esoteric version of libertarianism. You do neglect a large number (I would argue the strong majority) of libertarians who are consequentialists, such as Milton Friedman, James Buchannan, and Jagdish Bhagwati. You're right to start your story with Nozick, but wrong to end it there.

deleted and reposted

(1)

"mostly women, in forced marriages. Roughly a quarter of these slave are children. This slavery takes place in many forms; one form common in wealthier nations like the US is the exploitation of migrant workers." OK, this assertion on its own, I can accept for now… but wait a second, just before that you said "more than at any other time in human history"

But today's migrant workers (at least in the US, idk about Qatar) aren't subject to the same degree of total control and *literal* (i.e. actual, not metaphorical) institutional violence as black slaves pre-Civil War. If you change the definition of what constitutes slavery, then to be consistent you must at least attempt to estimate how many people in the past met your new definition of slavery: I highly suspect it's a lot more than whatever figures you got for historical slavery, which used old, more literal definitions of slavery.

(2)

Nice rhetoric on Elon Musk being the one ‘oppressed’ by taxes. That is striking and clearly something’s wrong!

At the same time your hypothetical feels like a strawman, not a steel man.

The problem with children mining cobalt is a more general problem with “sweatshop labor”, which is easy to decry but from an armchair it's easy to forget that things are inherently bad.

When you say “Of course no, nobody is pro-starvation”, I think actually you are wrong. I think that unless you propose a better solution, you *are* implicitly pro-starvation, and furthermore I think that’s a very important point.

Someone ‘in the arena’, making some difference, is just not morally comparable to someone on the sidelines.

And please don’t say ‘drawing attention’ is good enough; it rings hollow, because plenty of people have already drawn attention to ‘sweatshop labor’; that’s how it got its moniker. Yet what good have they done beyond that?

I think there’s a general problem where if somebody gets involved - ‘entangled’ - with some inherently messy problem in the real world, they are then seen as culpable for it, even if all they did was make it better. I think this is a point that is largely overlooked and it’s a point expounded beautifully here: https://blog.jaibot.com/the-copenhagen-interpretation-of-ethics/

(3)

I found it a bit offputting to read “while my co-contributor might not feel like reading books written by people he disagrees with”, because I subscribed specifically because I believe your co-contributor is a careful thinker and a great writer. I, too, choose not to read a vast array of books I “disagree with”, such as books on ancient aliens. Maybe your post could've used further revisions before publication.

I enjoyed many aspects such as the effective rhetoric suggesting the absurdity of thinking Elon Musk oppressed while not his poorest workers.