How the "biggest man-made medical disaster ever" impacts us today

From miracle drug to international heartbreak: the story of thalidomide

In 1954 a miracle drug was invented. Marketed as capable of treating headaches, flus, colds, anxiety, and morning sickness, it would cure the world. Tens of millions of pills were distributed, and the drug’s manufacturers made hundreds of millions of dollars from their panacea. There was only one problem: the creation and distribution of thalidomide was the largest man-made medical disaster in human history.

Background

Thalidomide was developed and released by German pharmaceutical company Grünenthal in 1954. It was marketed as a miracle drug — a cure-all for anxiety, colds, the flu, nausea, and morning sickness. As was usual at the time, the drug was introduced to the market after rodent testing found it to be non-toxic. No tests on human subjects were conducted before its approval by the West German government and subsequent export overseas.

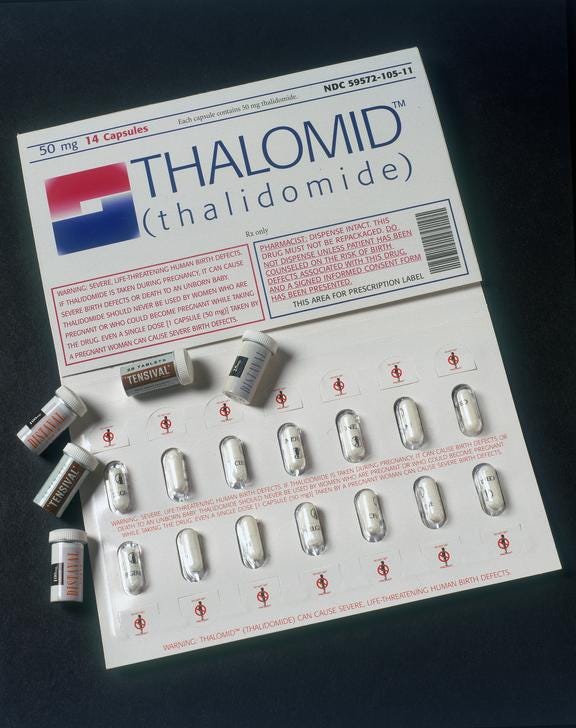

By the late fifties, thalidomide was marketed by 14 pharmaceutical companies under 37 names. In the UK, thalidomide was produced by The Distillers Company under the names Tensival, Valgraine, Asmaval, and Distaval. Despite never being tested on pregnant women, their ads claimed that “Distaval can be given with complete safety to pregnant women and nursing mothers without adverse effect on mother or child.” This could not be further from the truth.

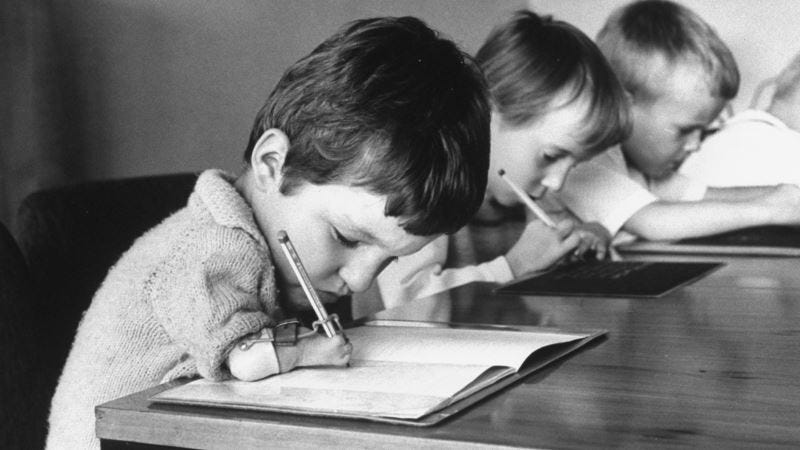

Between 1957 and 1961, over 20,000 babies were born with disabilities caused by thalidomide. When taken by pregnant people 20-37 days after conceiving, thalidomide causes abnormalities in the development of a fetus’ brain, eyes, and ears. Another common symptom of thalidomide exposure in the womb is phocomelia — ancient Greek for “seal limb”. Over 10,000 “thalidomide babies” were born with underdeveloped or missing arms and legs, and most of these children died before their first birthday. Thalidomide was taken off shelves around the world before the end of 1961, but already Grünenthal had created what many scientists call “the biggest man-made medical disaster ever.”

Early Complaints

To this day Grünenthal claims no legal liability and has never compensated thalidomide babies outside West Germany. However, in 2012, more than 50 years after the thalidomide tragedy, Grünenthal issued an apology to victims in the UK. As a part of their apology, senior executives of the company stated that they were acutely aware of the physical harm and emotional stress caused by thalidomide but hoped survivors could understand that Grünenthal did not know about the effects of thalidomide on infants before the release of the drug. While drug testing at the time was not as rigorous as regulatory standards require today (more on that below), it’s not entirely true that Grünenthal had no reason to believe their drug was unsafe.

Grünenthal was aware of warnings from doctors around the world that thalidomide was linked with tremors and birth defects as early as 1959, yet did not publicize this information. In 1960, Dr. Alexander Florence had a letter published in the British Medical Journal which claimed that a number of his patients had developed severe paranesthesia, a numb, burning sensation similar to pins and needles, after taking thalidomide. At this time Grünenthal was relentlessly pressuring the FDA to approve thalidomide despite a lack of evidence disproving the link between thalidomide and nerve damage. Later, Dr. William McBride wrote a letter to The Lancet noting that 1 in 5 women in his care taking thalidomide gave birth to children suffering from severe intellectual and physical disabilities. Soon after, Grünenthal employees refused to take thalidomide, fearing reports of serious side effects; Grünenthal wouldn't take the product off shelves for another six months.

The tragedy consumed public attention around the world, with women on every continent save for Antarctica being affected. However, notably, very few thalidomide babies were born in the US. While there were most likely more cases that haven’t been reported, officially only 17 thalidomide babies were born in the US. Thousands of lives were saved due to the work of one heroic FDA employee.

Enter Dr. Frances Kelsey

Frances Oldham Kelsey was born in 1914 in Vancouver Island, British Columbia. She grew up in the countryside, where she collected everything from bugs to birds’ eggs. Her inquisitive nature was put to good use when she graduated high school at only 15 years old, going on to get a master's in pharmacology before turning 22. At this time, women were rarely given opportunities to attend graduate school or conduct university-level research. However, at the behest of one of her professors at McGill, Kelsey wrote to Dr. M. K. Geiling, a noted researcher at the time, to ask for a job at the newly founded University of Chicago department of pharmacology.

Geiling read her letter, saw her impressive credentials, and immediately wrote back offering her a research position and scholarship — but there was a miscommunication. Geiling was unaware of the difference between Frances and Francis and assumed that Dr. Kelsey was a man. Frances considered writing back to explain that Frances with an “e” is female, but her professor disagreed with the idea. “Don’t be ridiculous,” he said, “Accept the job, sign your name, put 'Miss' in brackets afterward, and go! In her memoir Autobiographical Reflections, Kelsey wondered “if my name had been Elizabeth or Mary Jane, whether I would have gotten that first big step up.” While we may never be able to answer that question, we do know that if Dr. Frances Kelsey had not been offered that position, tens of thousands of American lives would have been in grave danger.

Battles With Thalidomide

When Kelsey first began working for the FDA in 1960, she was part of a small team of regulators. The FDA had only a fraction of the power it has today, and there were only seven full-time market reviewers on staff. One of Kelsey’s first assignments was reviewing the application for Kevadon, the first thalidomide pill to apply for approval in the US. It was supposed to be an easy assignment. Thalidomide was already widely used in Europe, and the drug’s American manufacturers expected it to breeze through the approval process.

However, Kelsey noticed inconsistencies between reports of the drugs’ effectiveness and the data collected while testing thalidomide. Despite being sold as a sedative and morning sickness prevention, there was no proof that the drug actually put animals to sleep. Moreover, manufacturers failed to provide sufficient evidence of the drug’s safety. They tried going over Kelsey’s head, appealing to her superiors, but she wouldn’t budge. Rather, after reading Dr. Alex Florence’s letter that claimed thalidomide causes serious nerve damage, Kelsey dug her heels in deeper. She correctly hypothesized that due to its paralytic nature, thalidomide use would result in “great harm to the developing embryo.”

Kelsey was vindicated on March 8, 1962, when the application was pulled in light of the newly unearthed effects of thalidomide on unborn children. She was heralded as a national hero, becoming the second woman to be awarded President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. At the ceremony, President John F. Kennedy lauded her accomplishments.

Dr. Kelsey, her exceptional judgment in evaluating a new drug for safety for human use, has prevented a major tragedy of birth deformities in the United States. Through high ability and steadfast confidence in her professional decision, she made an outstanding contribution to the protection of the health of the American people. I know that we are all most indebted to Dr. Kelsey. The relationship and the hopes that all of us have for our children, I think, indicate to Dr. Kelsey, I am sure, how important her work is and those who labor with her to protect our families. So, Doctor, I know you know how much the country appreciates what you have done. -JFK, at the medal awarding ceremony, Aug. 17, 1962

Much-Needed Reforms

Dr. Kelsey continued to work at the FDA until 2005, but her second most important professional accomplishment came only a year after her first. In 1962 she played a key role in shaping the Kefauver Harris Amendment, also known as the Drug Efficacy Amendment. Before the amendment’s passing, drug companies only had to show that drugs were safe for human consumption before they would be approved by the FDA, and even then, there was little oversight to how testing was conducted. The Drug Efficacy Amendment, however, established a “proof-of-efficacy” requirement — for the first time drug manufacturers were required to prove their drugs worked as intended before mass distribution.

We see the ramifications of this amendment all around us, particularly when we look at the FDA’s response to Covid-19. Many have criticized the FDA for being hesitant to approve Covid vaccines and tests; they claim that the FDA’s testing requirements are too strict and that they have led to delays in rolling out life-saving medicines. For example, some reliable rapid tests for Covid-19 were available for mass production just weeks into the pandemic, but continue to be denied approval by the FDA due to unclear, shifting requirements. At the same time, the FDA plays an important role in ensuring we can trust our health care providers. When the FDA loosened certification requirements for antibody tests in February last year, inaccurate tests flooded the market, resulting in consumer fraud and increased rates of Covid transmission. Every day the FDA walks on a tightrope, looking for the sweet spot between over-regulation and under-protection. The Drug Efficacy Amendment, inspired by the thalidomide scandal, was one of the agency’s first steps.

The government’s response to the pandemic has been one of the most contentious political issues in American history. Even now, with vaccines rolled out and testing (slowly) becoming more available, there are raging debates over the role of the FDA, CDC, and federal government in our daily lives. While thalidomide has played a key role in the establishment of these regulatory bodies, the thalidomide scandal also played a large role in the debate over the only medical procedure more politically contentious than the vaccine: abortion.

Thalidomide, The Vatican, and Children’s TV

In July 1962 Sherri Chessen, host on the Phoenix-area children’s TV show Romper Room, decided to get an abortion. She was three months pregnant with what was going to be her fifth child, but she feared the fetus’ life was in danger. While chaperoning a school trip to England Chessen’s husband bought some over-the-counter sedatives. He took them home and not thinking about it, gave them to his wife. Two months later, Chessen realized that the pills she had taken contained thalidomide. After consulting with her physician, she decided to get an abortion.

Abortions in Arizona at the time were only legal in cases where the mother’s life was in danger. However, some exceptions were made when “a panel of physicians felt the birth of a baby would cause grievous mental and emotional trouble for the mother.” The panel at her local hospital approved the abortion, but a hospital administrator canceled the procedure, fearing a potential lawsuit. In response, the hospital filed a suit in Maricopa County Superior Court — maybe a judge’s order would allow the abortion to continue. There was one downside to filing in court; Chessen would have to be mentioned by name in legal documents. The day after filing, her name and face were on the front page of the Arizona Republic.

Chessen immediately faced backlash from the Republic’s readers, receiving letters and phone calls criticizing her decision. Even worse, after her story made national headlines she lost her job, the Vatican released an official statement denouncing her, and the FBI was called in to protect her from credible death threats. However, despite public outcry, Chessen’s saga marked an important turning point in abortion rights. At the time, abortion was rarely discussed in public, and when it was, women who got abortions were painted as morally repugnant and distant from higher society. Chessen didn’t fit this narrative — she was a well-off, white woman from the suburbs who hosted a children’s TV show, anything but the caricature anti-abortion groups tried to paint her as. Most people supported her decision, and by 1965 77% of Americans wanted abortion legalized in cases where the mother’s life was in Chessen’s story evoked sympathy from much of mainstream America, and some historians believe her publicized difficulties in acquiring an abortion led to the creation of the American abortion reform movement.

Chessen was eventually able to get her abortion, but not in the US. The judge found that he did not have the authority to give a verdict on the case, so Chessen sought one overseas. A Swedish medical board approved her request on August 16, 1962, a month after Chessen first realized she had taken thalidomide. She had the abortion the next day.

Continuing Effects

Despite being pulled from shelves 60 years ago; we see the effects of thalidomide all around us. From our regulatory response to Covid to current abortion law, we can trace much of the world around us to the scandal. However, nothing embodies the human cost of the thalidomide tragedy more than the survivors themselves.

Many activists in the UK and US demand compensation to cover their medical expenses caused by thalidomide exposure. Aside from the costs of prosthetics and wheelchairs, thalidomide babies born in the early sixties are in their sixties already, and they face increased healthcare and eldercare costs due to their disabilities. In 2014, Australian survivors received an $89 million settlement from thalidomide’s Australian distributor. In the legal battle leading up to the settlement, many documents were uncovered suggesting that Grünenthal knew more about thalidomide’s effects than it let on, and this has encouraged activists in the UK to pursue compensation themselves.

While officially there were very few thalidomide babies born in the US, over 2.5 million thalidomide tablets were distributed across the country as part of clinical trials before FDA approval. Dozens of people born with disabilities similar to those induced by thalidomide seek recognition and assistance for their ailments, believing them to be caused by the drug. These survivors know that thalidomide is anything but a panacea. The drug certainly didn’t cure the world, but it did change it forever.

Illuminating and well-written article bro

Cool post, the historical tie in with abortion was especially interesting.

The defense of more stringent FDA approval standards is lacking however, because it only considers Type I errors of approving a dangerous drug. The Type II invisible graveyard of all the people who have suffered and died without medicines that were waiting on approval or not even developed due to the high costs of FDA approval is large. No one gets a presidential award for approving a drug that works.

This tradeoff is difficult to quantify but an attempt could be made. With vaccine approval timelines alone, we know that hundreds of thousands of lives could have been saved with faster approval. This already outweighs thalidomide but there are many more examples in both categories.